Understanding inflammation and the inner ear

Studying inflammation and the inner ear, researchers at Washington University hope to better understand hearing loss and disease

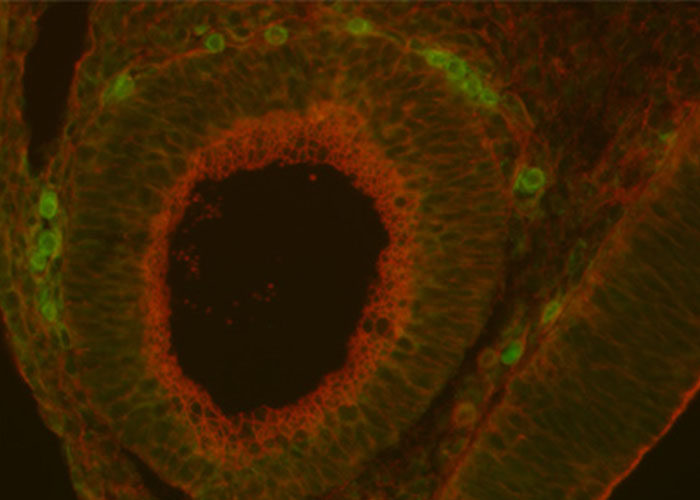

Macrophages are immune cells that are involved in the inflammatory process. Here the macrophages (shown in green) are present in a mouse embryo 10 days after fertilization, at the very beginning of inner ear development, which suggests an important role for these cells during formation of the inner ear.

The body’s inflammatory response to infection can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, immune cells are necessary to fight off foreign invaders. But in some cases, the body’s own defenses can actually cause damage. Washington University otolaryngologist Keiko Hirose, MD, is concerned about hearing loss associated with immune cells that find their way to the inner ear when they are not strictly needed there.

“Like the blood-brain barrier, the inner ear has ways to exclude immune cells from getting in when it would be better for them to stay out,” Hirose said. “Damage can occur in the inner ear when that regulation isn’t properly managed.”

In an effort to better understand the role of the immune system in hearing loss, Hirose and her colleagues are studying the effect of inflammation on the inner ear and are working to develop techniques to monitor the health of the blood-labyrinth barrier, the boundary separating the blood from the inner ear.

“My work is intended to improve our understanding of how the immune system interacts with the inner ear,” said Hirose, who sees patients at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. “At some future point, it may inform how we treat the inner ear with medications. But for now it is geared toward gaining a better understanding of what causes disease and its progression.”

Antibiotics and hearing loss

In one recent study, Hirose and her colleagues mimicked an inflammatory infection by injecting mice with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a bacterial component. Then, as might typically be done to treat a bacterial infection, the researchers gave the mice an antibiotic. In this case, the antibiotic was chosen because it is known to damage hearing. They found that mice given LPS plus the antibiotic had worse hearing loss than mice given the antibiotic alone.

“When these antibiotics are given to an animal, they suffer hearing loss,” Hirose said. “Our work is first to show that if they have bacterial components in the blood at the time of antibiotic treatment, their hearing loss is substantially worse.” The researchers thought the body protects the inner ear from such inflammatory reactions that are occurring elsewhere in the body. But this study suggests it’s not as protected they thought, she adds.

In another recent study, Hirose and colleagues report their development of a much-needed method to evaluate and quantify the chemicals in the blood that make their way into the inner ear.

“There is a large body of work that describes what the blood-brain barrier is doing,” Hirose said. “But no similar measures exist for the inner ear.”

Investigating the blood-labyrinth barrier

Hirose’s technique involves injecting a fluorescent dye into the blood, then sampling fluid from the inner ear to determine how much of the dye has penetrated the blood-labyrinth barrier.

“In control mice, we found that between 2 and 10 percent of the dye gets into the inner ear,” she said. “But when the mice are exposed to LPS first, a much higher percentage penetrates — between 10 and 40 percent. This is an important technique because it can give us a handle on when the barrier is open or closed, and how that affects hearing function.”

Such information could also help in understanding the relationship between inflammation and cochlear implants, devices implanted within the inner ear to help with hearing. As a cochlear implant surgeon, Hirose says she is interested in understanding how the immune system interacts with the implant.

“Understanding inflammation is very important in these scenarios,” she said. “It could help us do a better job of putting in these implants and anticipating how the immune system will respond to them. Also, this work could help us in preventing progressive hearing loss generally.”