Sleep deprivation accelerates Alzheimer’s brain damage

Study in mice, people explains why poor sleep linked to Alzheimer’s

Getty Images

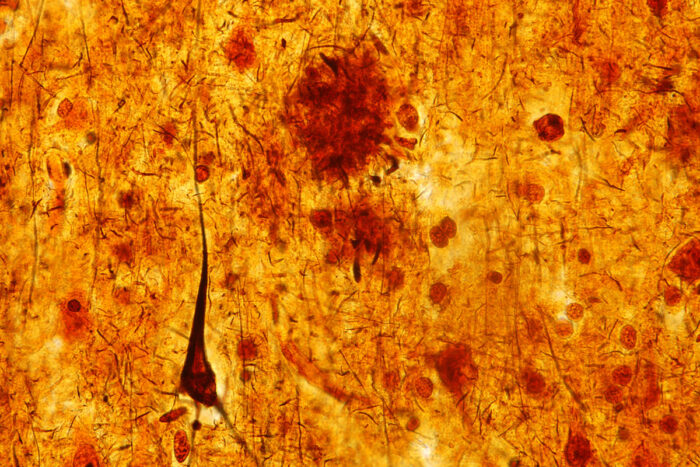

Getty ImagesA slice of brain tissue from a person who died with dementia shows an elongated brown triangle – a toxic tangle of tau protein associated with Alzheimer's disease and brain damage. A study in mice and people from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis shows that sleep deprivation causes tau levels to rise and tau tangles to spread through the brain, accelerating Alzheimer's brain damage.

Poor sleep has long been linked with Alzheimer’s disease, but researchers have understood little about how sleep disruptions drive the disease.

Now, studying mice and people, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that sleep deprivation increases levels of the key Alzheimer’s protein tau. And, in follow-up studies in the mice, the research team has shown that sleeplessness accelerates the spread through the brain of toxic clumps of tau – a harbinger of brain damage and decisive step along the path to dementia.

These findings, published online Jan. 24 in the journal Science, indicate that lack of sleep alone helps drive the disease, and suggests that good sleep habits may help preserve brain health.

“The interesting thing about this study is that it suggests that real-life factors such as sleep might affect how fast the disease spreads through the brain,” said senior author David Holtzman, MD, the Andrew B. and Gretchen P. Jones Professor and head of the Department of Neurology. “We’ve known that sleep problems and Alzheimer’s are associated in part via a different Alzheimer’s protein – amyloid beta – but this study shows that sleep disruption causes the damaging protein tau to increase rapidly and to spread over time.”

Tau is normally found in the brain – even in healthy people – but under certain conditions it can clump together into tangles that injure nearby tissue and presage cognitive decline. Recent research at the School of Medicine has shown that tau is high in older people who sleep poorly. But it wasn’t clear whether lack of sleep was directly forcing tau levels upward, or if the two were associated in some other way. To find out, Holtzman and colleagues including first authors Jerrah Holth, PhD, a staff scientist, and Sarah Fritschi, PhD, a former postdoctoral scholar in Holtzman’s lab, measured tau levels in mice and people with normal and disrupted sleep.

Mice are nocturnal creatures. The researchers found that tau levels in the fluid surrounding brain cells were about twice as high at night, when the animals were more awake and active, than during the day, when the mice dozed more frequently. Disturbing the mice’s rest during the day caused daytime tau levels to double.

Much the same effect was seen in people. Brendan Lucey, MD, an assistant professor of neurology, obtained cerebrospinal fluid – which bathes the brain and spinal cord – from eight people after a normal night of sleep and again after they were kept awake all night. A sleepless night caused tau levels to rise by about 50 percent, the researchers discovered.

Staying up all night makes people stressed and cranky and likely to sleep in the next chance they get. While it’s hard to judge the moods of mice, they, too, rebounded from a sleepless day by sleeping more later. To rule out the possibility that stress or behavioral changes accounted for the changes in tau levels, Fritschi created genetically modified mice that could be kept awake for hours at a time by injecting them with a harmless compound. When the compound wears off, the mice return to their normal sleep-wake cycle – without any signs of stress or apparent desire for extra sleep.

Using these mice, the researchers found that staying awake for prolonged periods causes tau levels to rise. Altogether, the findings suggest that tau is routinely released during waking hours by the normal business of thinking and doing, and then this release is decreased during sleep allowing tau to be cleared away. Sleep deprivation interrupts this cycle, allowing tau to build up and making it more likely that the protein will start accumulating into harmful tangles.

In people with Alzheimer’s disease, tau tangles tend to emerge in parts of the brain important for memory – the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex – and then spread to other brain regions. As tau tangles mushroom and more areas become affected, people increasingly struggle to think clearly.

To study whether the spread of tau tangles is affected by sleep, the researchers seeded the hippocampi of mice with tiny clumps of tau and then kept the animals awake for long periods each day. A separate group of mice also was injected with tau tangles but was allowed to sleep whenever they liked. After four weeks, tau tangles had spread further in the sleep-deprived mice than their rested counterparts. Notably, the new tangles appeared in the same areas of the brain affected in people with Alzheimer’s.

“Getting a good night’s sleep is something we should all try to do,” Holtzman said. “Our brains need time to recover from the stresses of the day. We don’t know yet whether getting adequate sleep as people age will protect against Alzheimer’s disease. But it can’t hurt, and this and other data suggest that it may even help delay and slow down the disease process if it has begun.”

The researchers also found that disrupted sleep increased release of synuclein protein, a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease. People with Parkinson’s – like those with Alzheimer’s – often have sleep problems.