Revealing the mysteries of early development

Zebrafish shed light on birth defects, cancer treatment

Jiakun Chen

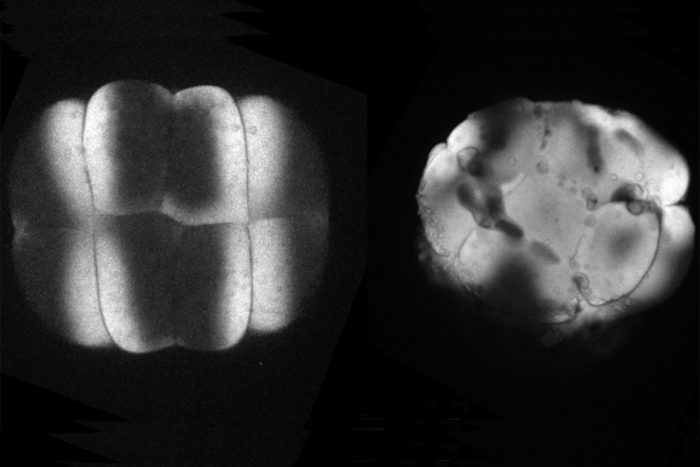

Jiakun ChenDeveloping zebrafish embryos offer clues to understanding human health. Comparing cell division in normal embryos, such as the one on the left, to cell division in embryos lacking a key protein, such as the embryo on the right, may shed light on the origin of some birth defects.

Zebrafish embryos are transparent and develop outside the mother’s body, enabling scientists to get a detailed view of early development. A research team led by Lila Solnica-Krezel, PhD, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor and head of the Department of Developmental Biology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, is revealing new clues to how birth defects develop in the tiniest embryos. Solnica-Krezel explained her lab’s recent work, published in the journal Developmental Cell.

What did you set out to study?

We know that some birth defects develop very early in embryonic development. We were especially interested in proteins called giant cadherins that are responsible for making cells stick together to form tissues. In recent years, scientists have started to link these molecules to human birth defects, such as abnormal brain development and abnormal heart development. Van Maldergem syndrome, for example, is a neurological condition associated with abnormal giant cadherins. Some heart valve defects also have been linked to problems with giant cadherins. But we don’t understand how they’re involved in these conditions.

What did you discover?

We have shown that these proteins also are involved in cell division, a process essential to life. That was not suspected. It’s not that all cell division is stopped when giant cadherins are defective or absent, it’s that a fraction of cell divisions are abnormal. The embryo keeps developing, but maybe 10 to 20 percent of cell divisions are abnormal. We suspect this may be why people haven’t noticed it before. It’s not an absolute block of cell division. But some cells divide into three, for example. This is not normal — a cell should divide in two. Otherwise, the genetic material is not partitioned correctly.

We also found that in normal cells, structural elements of the cell that carry out cell division are constantly turning over at a specific rate in a very dynamic manner. But in zebrafish mutant embryos that lack giant cadherins, graduate students in my lab, including Jiakun Chen and Gina Castelvecchi, showed that the turnover of these structural elements is sluggish. This may be part of why their cell division is abnormal.

Why is this important?

In addition to helping us understand the origin of some birth defects, we were surprised to be able to link our discoveries to current cancer therapies.

We found through collaboration with Helen McNeill, PhD, a professor of developmental biology and one of our BJC Investigators, that at least one way this giant cadherin affects structural elements of cells is through binding to a protein called Aurora B. This protein is required for cell division across species, from fruit flies and zebrafish to mammals, including people. Because tumor cells divide faster than normal cells, drugs against Aurora B are common cancer therapeutics. Our study potentially identifies additional molecules that could be targeted by cancer drugs.