Regenerating heart tissue: a targeted approach

Washington University is part of a nationwide trial to improve on the use of stem cells in repairing damaged heart muscle

Washington University School of Medicine is among 16 sites nationwide participating in a clinical trial of a procedure aimed at improving on past attempts to use stem cells to heal damaged heart muscle. The STOP-HF Trial is a phase II efficacy study intended for severely impaired heart failure patients who have exhausted conventional therapy, such as bypass surgery, angioplasty and the most intensive medical therapy.

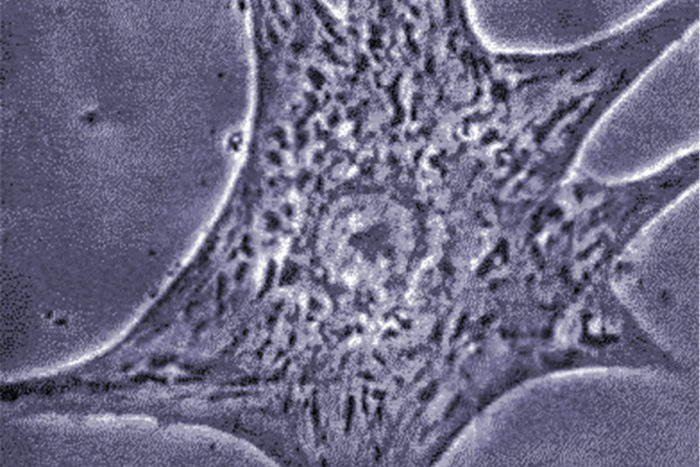

In the procedure, cardiologists use a specialized catheter inserted in the groin to inject a drug—a piece of DNA—directly into the tissue of the heart’s left ventricle, targeting areas that have the potential for growth and development. Once the drug is inserted, it induces secretion of stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), a protein known to attract stem cells and progenitor cells, both of which have the ability to transform into the cell types of surrounding tissue.

Providing better options

“We’re doing this trial to provide better options for our patients with poor heart function,” says John Lasala, MD, PhD, medical director of the Washington University Cardiac Catheterization Lab at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “The hope is that these cells can develop into new heart cells or into blood vessel cells to provide more blood flow to the area.”

The procedure is performed under conscious sedation with local anesthetic. Afterwards, patients are up and moving around within four to six hours but are kept in the hospital overnight as a precaution.

The idea of using stem cells to regenerate tissue in the heart is not new. Lasala says other approaches are more cumbersome and involve giving patients an injection to stimulate the growth of stem cells, harvesting those cells and then giving them back to the patient, either into the heart or the circulation. The results have been modest at best, he says.

“A key finding of the previous trials was that the percentage of stem cells that actually took up residence in the heart was very small,” Lasala explains. “So we’re trying to find a more efficient way to get stem cells right where we need them so they can do more good.”

In this trial, which is no longer seeking participants, researchers are studying the response to various doses. Participants are randomized to either placebo or two different doses of the DNA. The hope is that the response will be in proportion to the dose.

“Patients are evaluated with a six-minute treadmill walk test before treatment and again six months after. If the patient is able to walk further, more comfortably six months after treatment, then we know there is real promise here,” Lasala says.

“We’ve been down this pathway before and had several false starts,” Lasala adds, “but despite those false starts we are still optimistic that this type of therapy will be successful in the future.”

This trial is sponsored by Juventas Therapeutics, manufacturer of the DNA tested in the STOP-HF Trial.