Protecting memory

Washington University physicians are applying the principles of preventive medicine to their research into Alzheimer’s disease

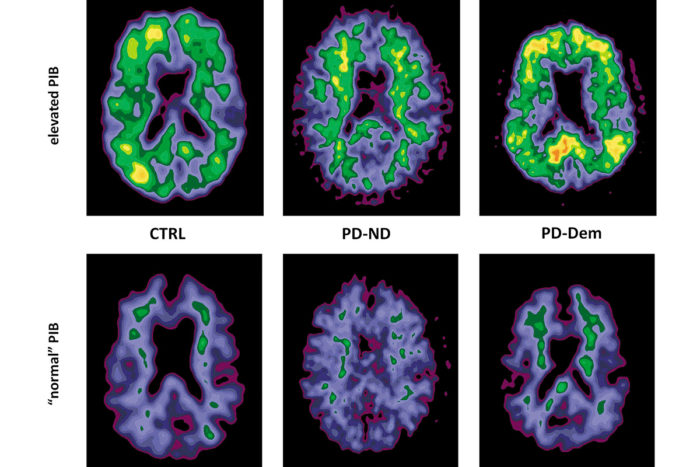

A new imaging agent, Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB), binds to proteins in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s and gives off a visible signal.

Collaborators within the Charles F. and Joanne Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (Knight ADRC) at Washington University School of Medicine are developing ways of identifying patients at risk for Alzheimer’s disease years before dementia symptoms begin. They believe that beginning preventive treatment before brain damage occurs is essential to halting the progression of this devastating disorder.

The ADRC is one of only 32 federally designated centers dedicated to fostering innovative Alzheimer’s research, and the only such center in Missouri.

Unraveling the puzzle of Alzheimer’s

“As recently as the 1980s, we were unable to tell whether patients truly had Alzheimer’s disease until they died and the brain was examined at autopsy,” says John C. Morris, MD, director of the ADRC. “Although definitive diagnosis still requires an autopsy, there has been an explosion of knowledge about the disease over the past 30 years.”

Researchers now know that Alzheimer’s disease is caused by a build-up of particular proteins in the brain, which results in plaques and tangles.

As more and more of these plaques and tangles develop in certain areas of the brain, healthy nerve cells work less efficiently, gradually lose their ability to communicate with each other and eventually die. This leads to the cognitive impairments associated with the disease.

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s in the living brain

Perhaps the most startling, and at the same time promising, discovery made to date about Alzheimer’s is that brain plaques likely begin to develop years before symptoms arise and may have a genetic component. Much of the evidence supporting this conclusion has been uncovered at Washington University.

“We represent the leading group in the world using cutting-edge technologies that allow us to identify during life the changes in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s disease,” says David M. Holtzman, MD, Barnes-Jewish neurologist-in-chief and chairman of neurology at Washington University. One new method of gauging changes in the brain involves collecting spinal fluid through a lumbar puncture.

“The spinal fluid is made up of material coming directly from the cells in the brain,” says Holtzman. This fluid can help identify the changes that occur in proteins involved in the disease while people’s cognitive abilities are still normal. He adds, “Over the next five to 10 years, this test has the potential for being integrated into a regular doctor’s office visit. At a certain age, patients would get a spinal tap, these proteins would be assessed, and their relative risk for the disease revealed.”

Another promising screening for the disease involves the use of a new imaging agent, Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB), during positron emission tomography (PET) imaging scans.

“The unique aspect of the PiB agent is that when it is injected into the vein, it travels to the brain, recognizes the abnormal proteins associated with Alzheimer’s, binds to them and gives off a signal that is readily visible through the PET scanner,” explains Morris. This imaging likely will allow diagnosis of the disease 10 to 20 years before symptoms appear and intervention with preventive medications to slow or stop the disease’s progression. “Our hope is that if we begin prescribing these drugs well before this damage begins, they will be more effective in stopping the disease’s progress.”

The Adult Children Study: Learning from the next generation

Integral to the research being conducted by ADRC researchers is the Adult Children Study, which was begun in 2005 and is funded through a major grant from the National Institute on Aging. Two groups of volunteers between the ages of 45 and 74—one group whose members had a parent with Alzheimer’s, the other group whose parents did not have the disease—are undergoing diagnostic tests over many years’ time. The testing ranges from cognitive evaluations to examining spinal fluid and PET scans for markers of the disease. Researchers will be taking these measurements multiple times every two to three years. This will allow them to determine any changes in individuals over longer periods of time.

“The participants in the Adult Children Study are the most dedicated and highly motivated research volunteers you could want. And it’s because they have seen Alzheimer’s disease in their parent,” says Morris.

“Most of them participate because they want to help, if not themselves, certainly others such as their children.”

A volunteer’s perspective

Dianne Kerley, 55, watched both her grandmother and mother slowly slip away as they succumbed to the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

“My mom was diagnosed with possible Alzheimer’s disease when she was 64 in 1993. She passed away in 2008. Throughout those 15 years we watched as she drew into herself and lost her memories of her older adult life,” says Kerley. “Eventually she didn’t remember my dad and didn’t recall that she had a younger brother.”

As do many adult children of Alzheimer’s patients, Kerley also experienced the reversal of roles required as a caregiver. “I ended up taking on a parenting role with her, especially after my dad died,” she says.

Kerley’s greatest wish is that her son will not have to experience the same sense of loss and responsibility with her. For that reason, she was one of the first volunteers in the Adult Children Study being conducted by the ADRC.

“We want to be a part of making this world better for our children and grandchildren by helping to discover ways of stopping the progression of—or better still, eliminating—this disease,” Kerley says.

Editor’s note: The Adult Children Study is no longer recruiting participants.