Probiotic protects intestine from radiation injury

New research shows in mice that taking a probiotic before radiation therapy can protect the intestine from damage

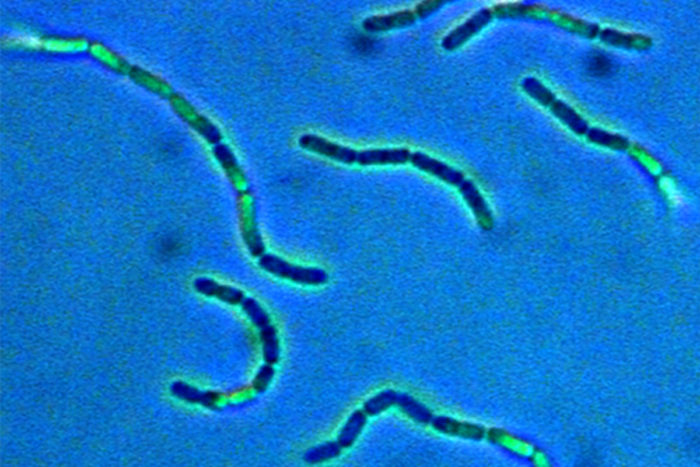

The probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG may protect the lining of the small intestine from radiation injury.

A study by Washington University School of Medicine researchers suggests that taking a probiotic may help mice and possibly also cancer patients avoid intestinal injury, a common problem in those receiving radiation therapy for abdominal cancers. The research is published online in the journal Gut.

Radiation therapy is often used to treat prostate, cervical, bladder, endometrial and other abdominal cancers. But the therapy can kill both cancer cells and healthy ones, leading to severe bouts of diarrhea if the lining of the intestine is damaged.

“For many patients, this means radiation therapy must be discontinued, or the radiation dose reduced, while the intestine heals,” says senior investigator William Stenson, MD, the Dr. Nicholas Costrini Professor in Gastroenterology and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. “Probiotics may provide a way to protect the lining of the small intestine from some of that damage.”

Probiotic protection

This study showed that certain strains of the probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus, including Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) protected the lining of the small intestine in mice receiving radiation.

“The lining of the intestine is only one cell-layer thick,” Stenson says. “This layer of epithelial cells separates the rest of the body from what’s inside the intestine. If the epithelium breaks down as the result of radiation, the bacteria that normally reside in the intestine can be released, travel through the body and cause serious problems such as sepsis.”

The researchers found that the probiotic was effective only if given to mice before radiation exposure. If the mice received the probiotic after damage to the intestinal lining had occurred, the LGG treatment could not repair the damage.

Because the probiotic protected intestinal cells in mice exposed to radiation, the investigators believe it may be time to study probiotic use in patients receiving radiation therapy for abdominal cancers.

Probiotic prevention

“In earlier human studies, patients usually took aprobiotic after diarrhea developed when the cells in the intestine already were injured,” says first author Matthew Ciorba, MD, a Washington University gastroenterologist. “Our study suggests we should give the probiotic prior to the onset of symptoms, or even before the initiation of radiation because, at least in this scenario, the key function of the probiotic seems to be preventing damage, rather than facilitating repair.”

The investigators wanted a carefully controlled study to evaluate the probiotic’s protective effects.

Previously, Stenson and his colleagues demonstrated that a molecular pathway involving an enzyme called cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), a key component in inflammation, could protect cells in the small intestine by preventing the cell death that occurs in response to radiation.

They gave measured doses of LGG probiotics to mice, directly delivering the live bacteria to the stomach. They found it protected only mice that could make COX-2. In mutant mice unable to manufacture COX-2, the radiation destroyed epithelial cells in the intestine, just as it did in mice that didn’t receive the probiotic.“In the large intestine, or colon, cells that make COX-2 migrate to sites of injury and assist in repair,” Ciorba says.“We believe this mechanism is key to the protective effect we observed.”

Human studies are beginning soon to test their research results. Patients will be offered a lactobacillus-based probiotic prior to and during radiation therapy for an abdominal or pelvic cancer. Over the course of treatment, researchers will monitor whether the probiotic therapy prevents radiation-associated gastrointestinal symptoms in these individuals. “This translation of research from bench to bedside is very exciting,” Ciorba says.

“The bacteria we use is similar to what’s found in yogurt or in commercially available probiotics,” he says. “So theoretically, there shouldn’t be risk associated with this preventive treatment strategy any more than there would be in a patient with abdominal cancer eating yogurt.”

In addition, he notes, future research is focused on isolating the particular protective factor produced by the probiotic. When that is identified, a therapeutic could be developed to harness the probiotic benefit without using the live bacteria.