Personalized immunotherapy for late-stage melanoma

New research uses late-stage skin cancer patients’ own immune cells to target their cancer. This work could lead to a personalized cancer vaccine

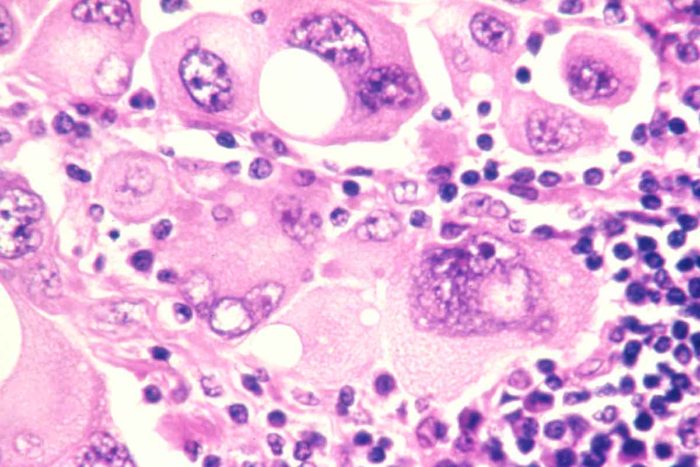

Melanoma cells. Image courtesy of National Cancer Institute.

The battle against metastatic melanoma is being waged on a new front. For the first time ever, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine are conducting a clinical trial coupling cancer genome sequencing with immune cell therapy. Their hope is that the combination will trigger a patient’s own immune system to mount a potent, targeted attack on the melanoma.

This proof-of-concept clinical trial began when seven participants were infused with immune messengers called dendritic cells that stimulate the immune system’s T cells to attack the cancer cells.

A Personalized Vaccine

“In principle, we are creating a personalized vaccine based upon the patient’s own cancer genome,” says principal investigator Gerald Linette, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine.

Malignant melanoma is difficult to treat because it spreads rapidly; fewer than 100 cells are required for the cancer to metastasize. Ten-year survival rates currently are less than 10 percent. The FDA has recently approved several drugs for melanoma—ipilimumab (Yervoy) and vemurafenib (Zelboraf), both of which increase survival rates. Yet most patients still die of advanced melanoma, so there is still an urgent need for better treatments.

For the past eight years, Linette, associate professor of medicine and of neurological surgery, and collaborator Beatriz Carreno, PhD, research associate professor in the Department of Medicine’s Division of Oncology, have focused on the use of immune cell therapy to treat melanoma. In a clinical study published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Linette and colleagues used dendritic cell therapy to treat stage IV melanoma.

Turning on T Cells

Dendritic cells are specialized antigen-presenting cells that serve to trigger the body’s cancer-killing T cells. Nobel laureate Ralph Steinman, MD, at the Rockefeller University in New York, initially discovered dendritic cells in 1973 and provided the scientific foundation to study dendritic cell vaccines in humans as a way to turn on tumor-specific T cells. In healthy people, T cells normally protect from viral and bacterial infections but also play an important role in controlling cancer.

In the study, Linette and colleagues activated dendritic cells from seven patients. After reintroducing these dendritic cells back into the patients, six of the seven had a positive T-cell response against their melanoma cells. Three of seven patients’ tumors shrunk significantly, with one of those patients going into complete remission and another patient demonstrating minimal disease after five years.

The response was met with immediate scientific interest because the process, if confirmed by others, could lead to new options to treat not only metastatic melanoma but also other cancers.

Personalized Gene Targeting

Linette’s current clinical trial takes the immune therapy approach one step further by targeting specific tumor genes. Working with Elaine Mardis, PhD, and colleagues at Washington University’s Genome Institute, Linette and Carreno are honing in on the unique melanoma “fingerprint” for each patient, using genomic information to generate a personalized immune cell therapy that targets unique changes, or mutations, within each person’s tumor.

“Immune cell therapy is a new class of therapeutics. Each dose is customized for every patient starting with blood cells grown in a specialized laboratory called the Siteman Biologic Therapy Core manufacturing facility,” says Linette. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania led by Carl June, MD, are reporting strong results using a similar approach for the treatment of leukemia, he notes.

Linette and Carreno are currently developing new methods to manufacture T cells specific for unique tumor mutations. Their goal is to eventually combine T cell therapy with ipilimumab and vemurafenib.

“I hope we’ll be curing some patients within the next 10 years and that melanoma will be treated more like a chronic illness than a deadly disease,” says Linette. “By using a combination of therapies that are truly targeted and personalized, patients can have a good quality of life. The future looks bright.”