Measuring damage to brain networks may aid stroke treatment, predict recovery

Functional MRI scans provide crucial data for stroke patients

Joshua Siegel

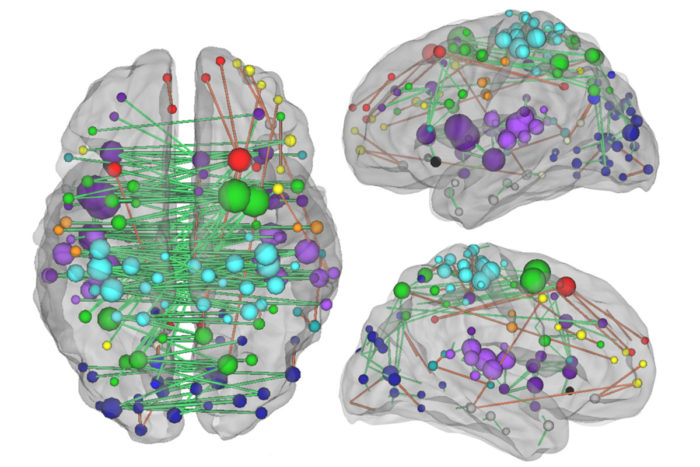

Joshua SiegelUnderstanding the network of connections between brain regions — as depicted above — and how they are changed by a stroke, is crucial to understanding how stroke patients heal, according to new research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Close to half a million people survive strokes every year in the United States, and many are left with long-term disabilities. The options for treatment, after the damage is done, are limited, and predicting who will recover and how much is an elusive goal.

Now, two new studies from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicate that current clinical practices may be missing a key aspect of stroke-induced brain damage. For some cognitive functions, such as memory and attention, the severity of a person’s disability correlates with the extent of disruption to the brain’s communication networks – something that is not measured by most brain scans.

One study is published online the week of July 11 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The other is available online in the Annals of Neurology.

“The holy grail of predicting stroke recovery is to develop an individualized algorithm that will reliably tell us, ‘This patient will recover 85 percent of his abilities and that patient only 55 percent,’” said Maurizio Corbetta, MD, the Norman J. Stupp Professor of Neurology and senior author on both studies. “If you’re trying to predict recovery for someone who has a sensory, motor or visual deficit, the scans we use today provide a lot of information. But if the patient has a memory or an attention deficit, the scans do not give you much to work with.”

This research suggests that functional brain scans – those that measure damage to the brain’s communication network – may help predict recovery and guide treatment.

Joshua Siegel

Joshua Siegel

Corbetta, graduate student Joshua Siegel, and colleagues including Gordon Shulman, PhD, a professor of neurology, investigated whether a brain scan known as functional connectivity MRI (fcMRI) could provide more useful information for assessing stroke damage. They used fcMRI to assess communication between brain areas in 130 stroke patients and in 31 people who had not experienced strokes. The technology allowed them to identify large disruptions to brain communication that occurred as a result of stroke. They also gave each participant a battery of neuropsychological tests to measure vision, motor function, language ability, visual memory, verbal memory and attention.

The researchers found that the size and location of brain lesions correlated with vision and motor impairments, but problems with memory were better explained by changes to the networks of brain connections. Predicting attention and language deficits required knowing something about both the lesions and the networks.

“We showed that the approach doctors have been using for 130 years of mapping brain lesions to symptoms only gets you so far,” Siegel said. “For memory, it turns out that it’s not damage to a specific location that really matters but whether the connections between locations are intact.”

Currently, fcMRI is not used clinically, and the kinds of MRI and CT scans used to assess stroke damage don’t measure how well different brain regions work together.

“Functional MRI hasn’t been used in the clinic because, before this study, there wasn’t convincing evidence that these patterns of connectivity provide valuable information related to behavior,” Corbetta said. “Moving forward, we’ll need to conduct additional studies of many more patients to show that getting functional scans in the first hours or days after a stroke could provide valuable information for predicting outcome and tracking recovery.”

In a separate study, other researchers in the Corbetta lab evaluated what happens to damaged brain networks during stroke recovery. Do old pathways re-open, or are new pathways forged?

Graduate student Lenny Ramsey led research focused on neglect, a kind of attention deficit that affects about a quarter of all stroke patients. People with neglect simply do not notice part of their world. Given a plate of food, for example, a person with neglect will eat only part of it and stop, thinking the plate is empty.

Ramsey and colleagues studied 77 stroke patients with neglect and 31 adults of the same age who had not experienced strokes. The patients underwent fcMRI brain scans and completed a battery of neuropsychological tests at two weeks and and then three months after their strokes. The healthy adults also underwent two rounds of fcMRI scans and behavioral tests, spaced three months apart.

The researchers found that as the stroke patients’ symptoms of neglect lessened, the patterns of connections between parts of their brain became more similar to the patterns found in healthy people. The people with neglect who experienced the best recoveries came close to restoring normal patterns of connectivity.

“It was theoretically possible that the brain regions could recover by reorganizing and communicating in a new way, but that isn’t what we saw,” Ramsey said. “We think that the original networks form during early development to be as efficient as possible. So when a part gets damaged, in order to get back to normal functioning, you need to restore the old wiring. Nothing else is going to work as well.”

Shulman added, “Of course, under circumstances in which critical regions and pathways are severely damaged, reorganization may be the only option.”

The work suggests the possibility of treating brain damage by coaxing networks toward normal patterns of connections. Right now, treatment for stroke is centered on the first few hours, when rapid intervention with drugs or surgery can prevent brain tissue from dying. Once the damage is done, though, patients’ options are limited to behavioral interventions such as physical therapy.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has been used experimentally to aid stroke recovery. It involves sending magnetic waves through the skull and into the brain, causing an electrical current that stimulates neurons in the targeted area. While the effects of the technique are not well-understood, TMS may be able to restore normal connectivity by stimulating neurons to make more connections with each other, thereby enhancing communication between parts of the brain.

“In the past, TMS has been applied blindly in experimental stroke treatments, with no regard for what’s going on in brain connectivity,” Corbetta said. “Our goal is to use some of the techniques we’ve developed in these papers to map patterns of dysfunction in individual patients, and then use those maps to guide interventions to restore normal communication between brain regions.”