Exploring the brain-gut connection

Washington University gastroenterologists are studying how the brain and gut interact and may be linked to bowel issues

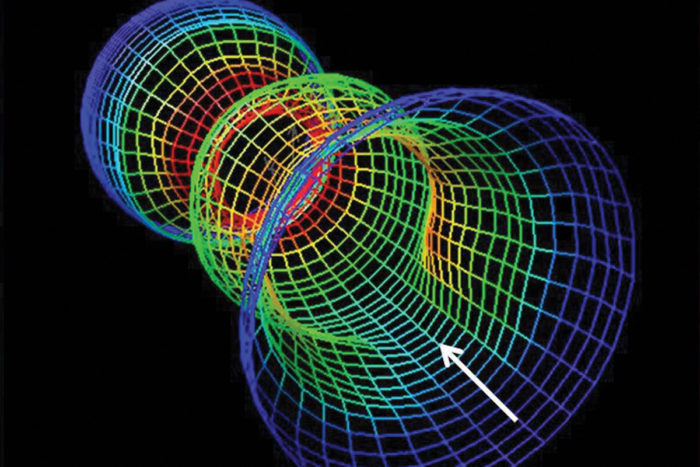

Gastroenterologists use high-resolution manometry, a technique to image and evaluate parts of the rectum (shown here) to evaluate patterns of muscle contraction.

It might seem like the brain is pretty far away from the gut, but for patients with functional bowel disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), much of the problem is, quite literally, in their heads.

For many years, investigators in the Washington University Division of Gastroenterology have been studying links between mind and body, particularly those involving the brain and the gut. David Alpers, MD, and the late Ray Clouse, MD, hypothesized that in many conditions, the activity in a patient’s brain was probably just as important as what was happening in their bowel.

Now, using specialized brain and gastrointestinal (GI) imaging, Washington University gastroenterologists are attempting to understand how the brain interacts with the enteric nervous system, an intricate network of nerves that runs through the wall of the intestines. Their work is demonstrating that those suspected links between the gut and the brain are real.

“I think intuitively most patients recognize that when they have a lot of stress in their lives, they’re more likely to have a worsening of their GI symptoms, things like butterflies in the stomach, for example,” says Gregory Sayuk, MD, a Washington University gastroenterologist. “The connection between the mind and body isn’t a foreign concept to doctors or to patients, but we’re really focusing on trying to better understand what actually lies behind this experience that patients have.”

Seeking the brain’s connection to the gut

Working with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and high-resolution manometry, which tests muscle function, Sayuk and others are attempting to understand exactly how the brain might be involved.

“Functional bowel problems like IBS are different than some other disorders,” explains Sayuk. “The word ‘functional’ itself implies that there’s nothing really wrong with the structure or the integrity of the bowel. It’s rather that the bowel doesn’t operate normally. But the brain is definitely a player in all of this.”

Sayuk uses fMRI scanning to watch the brain respond to signals that come from the gut. In one of his ongoing studies, IBS patients receive a scan while a balloon is inflated in the gut.

“Most people describe the sensation as similar to what it feels like when they have gas,” he explains. “But what we’re more interested in is how their brains are responding.”

Abdominal discomfort and anxiety

In other studies, Sayuk’s group is looking at what happens in the brain when people with and without IBS look at upsetting images designed to provoke an anxious response. He’s learning that many of the same brain regions that get activated in response to abdominal discomfort also are involved in anxiety in people who don’t have GI problems.

While Sayuk concentrates on brain imaging, gastroenterologist C. Prakash Gyawali, MD, looks at how parts of the digestive tract function in people with IBS, as well as in people with anxiety and depression. He uses high-resolution manometry to evaluate motor function in the esophagus and in the rectum; he’s learned that in the esophagus the patterns of muscle contraction are different in some patients, which may help explain why they develop symptoms.

“It could be that patients with these symptoms, including IBS patients, have a higher likelihood of abnormal contraction patterns,” Gyawali says We know, for instance, that people with these so-called ‘spastic’ patterns tend to have a higher frequency of functional disorders like IBS, as well as a higher incidence of psychiatric disorders like anxiety or depression.”

More spasms than normal

He says the same thing holds true at the other end of the GI tract, where people with IBS, depression and anxiety tend to have spastic patterns in the rectum. Although it’s not possible to use manometry studies to diagnose individual patients, Gyawali says IBS patients tend to have a more spastic pattern than healthy people. “These studies are helping us understand the changes in physiology that can accompany functional bowel disorders,” he says.

A potential treatment, say Gyawali and Sayuk, is antidepressant medication.

“We use a lot of antidepressants in IBS patients,” Sayuk explains. “We find them to be quite effective, and we literally have hundreds of patients receiving antidepressants for their bowel symptoms.”

It’s believed that about 15 percent of the people in the United States may have IBS, with three times as many women affected as men. Sayuk says most patients he sees have had symptoms for 8 to 9 years by the time they show up in his office. Sayuk believes the trigger that launches those symptoms probably isn’t located in the gut.

“We’re trained as gut doctors, and so we focus, naturally, on the patient’s symptoms and on trying to understand the bowel itself,” he says. “But I think we’ve come to recognize that that approach has left us wanting and has really fallen short of offering satisfactory explanations of what’s going on.”