Brain hardwired to respond to others’ itching

Researchers discover why mice scratch in response to other mice scratching

Michael Worful

Michael WorfulItching is a highly contagious behavior. When we see someone scratch, we're likely to scratch, too. New research from the Washington University Center for the Study of Itch shows contagious itching is hardwired in the brain.

Some behaviors — yawning and scratching, for example — are socially contagious, meaning if one person does it, others are likely to follow suit. Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that socially contagious itching is hardwired in the brain.

Studying mice, the scientists have identified what occurs in the brain when a mouse feels itchy after seeing another mouse scratch. The discovery may help scientists understand the neural circuits that control socially contagious behaviors.

The study is published March 10 in the journal Science.

“Itching is highly contagious,” said principal investigator Zhou-Feng Chen, PhD, director of the Washington University Center for the Study of Itch. “Sometimes even mentioning itching will make someone scratch. Many people thought it was all in the mind, but our experiments show it is a hardwired behavior and is not a form of empathy.”

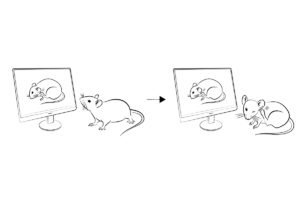

For this study, Chen’s team put a mouse in an enclosure with a computer screen. The researchers then played a video that showed another mouse scratching.

“Within a few seconds, the mouse in the enclosure would start scratching, too,” Chen said. “This was very surprising because mice are known for their poor vision. They use smell and touch to explore areas, so we didn’t know whether a mouse would notice a video. Not only did it see the video, it could tell that the mouse in the video was scratching.”

Next, the researchers identified a structure called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a brain region that controls when animals fall asleep or wake up. The SCN was highly active after the mouse watched the video of the scratching mouse.

WU Center for the Study of itch

WU Center for the Study of itchWhen the mouse saw other mice scratching — in the video and when placed near scratching littermates — the brain’s SCN would release a chemical substance called GRP (gastrin-releasing peptide). In 2007, Chen’s team identified GRP as a key transmitter of itch signals between the skin and the spinal cord.

“The mouse doesn’t see another mouse scratching and then think it might need to scratch, too,” Chen said. “Instead, its brain begins sending out itch signals using GRP as a messenger.”

Chen’s team also used various methods to block GRP or the receptor it binds to on neurons. Mice whose GRP or GRP receptor were blocked in the brains’ SCN region did not scratch when they saw others scratch. But they maintained the ability to scratch normally when exposed to itch-inducing substances.

Chen believes the contagious itch behavior the mice engaged in is something the animals can’t control.

“It’s an innate behavior and an instinct,” he said. “We’ve been able to show that a single chemical and a single receptor are all that’s necessary to mediate this particular behavior. The next time you scratch or yawn in response to someone else doing it, remember it’s really not a choice nor a psychological response; it’s hardwired into your brain.