Arthritis-causing virus makes its way to the U.S.

Mosquito-borne Chikungunya virus, which causes arthritis-like symptoms, has mutated to cause more severe infection with cases recently showing up in the U.S

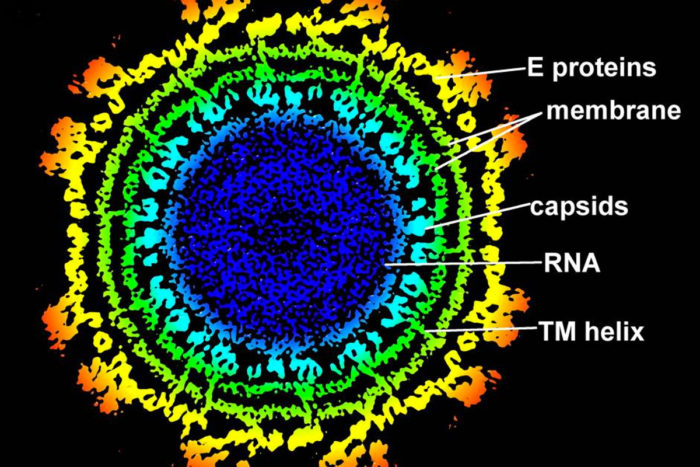

Cross-section of the Chikungunya virus. Image courtesy of eLife: (doi: 00435.003), Michael Rossmann and Siyang Sun, Purdue University.

Editor’s Note: This is a revision of a story that first appeared on March 14, 2014. For more information and updates on Chikungunya virus, please visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s page.

Chikungunya is a mosquito-borne virus that has caused outbreaks in Africa, Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, Southern Europe and most recently in the Caribbean. Acute symptoms include fever, rash and severe joint paint. Twenty to thirty percent of those infected go on to develop chronic arthritis that may last for years.

Chikungunya is an African word for “that which bends up,” describing the appearance of the severe arthritis the infection causes. First isolated in Tanzania in 1952, the virus was mainly spread by the tropical Aedes aegypti mosquito. Since then there have been periodic brief outbreaks in Africa and Asia.

More severe outbreak

In 2006 there was a more severe Chikungunya outbreak in La Réunion, a French island in the Indian Ocean. The virus infected one-third of the population, or 260,000 people. Researchers studying the La Réunion strain of the virus found that it had mutated and could now be transmitted by the Aedes albopictus, or Asian tiger mosquito, which is found in more temperate climates.

Normally the virus does not kill, instead causing acute arthritis-like symptoms or occasionally longer-term joint pain. But in the La Réunion outbreak, there were more than 250 deaths, which occurred mostly among the elderly; newborns also tended to have severe symptoms.

After the La Réunion outbreak, the virus spread throughout India, Malaysia and Thailand, then into Italy in 2007 and Southern France in 2010. In December 2013 it showed up for the first time in the Americas—on the Caribbean island of St. Martin, causing concern that its next stop would be the U.S.

Coming to the U.S.

By July 2014 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported two locally acquired cases in Florida and more than 600 travel-associated cases across the U.S., Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

“There is a high likelihood that there are going to be outbreaks throughout the U.S. as we have more and more travelers coming back infected with the virus,” says Deborah Lenschow, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist who studies Chikungunya virus. With no vaccine yet available in a population that has no existing immunity to the virus, the infection has the potential to spread widely.

By studying mouse models of the La Réunion strain and an older strain isolated from Senegal, Lenschow and others have been working to identify what might be responsible for the virus’ spread and increased severity. They found that both strains were able to infect connective tissue surrounding muscle fibers. But only the La Réunion strain could infect myofibers, cells found within muscles, resulting in much higher viral levels and increased muscle damage. Ongoing research will determine whether specific mutations, or changes, in the virus that allow myofiber infection could help to explain the increased disease severity seen in La Réunion.

Lenschow and colleagues also wanted to understand why La Réunion newborns had more severe symptoms than older individuals. Studying patients from La Réunion, they determined that newborns mounted as good as, if not a stronger, response to the virus than adults. Further work in a newborn-mouse model suggests that a key gene involved in the patients’ response to viral infection, ISG15, may play a role in explaining the severity of disease in the human newborns; when exposed to the La Réunion strain, mice lacking this gene produce an exaggerated cytokine response, which can lead to severe inflammation similar to that seen in the La Réunion newborns infected with Chikungunya.

“If we can understand mechanistically how the immune system is regulating this response, we may be able to find a way to dampen it or prevent it altogether,” says Lenschow.

Chikungunya infection

What to watch for

- Acute symptoms usually begin three to seven days after being bitten by an infected mosquito and generally last about a week

- Common symptoms include: fever, severe joint pain, joint swelling, headache, nausea, fatigue, muscle pain and rash

- Chronic symptoms include longer-term joint pain, more commonly found in the elderly

- Newborns may develop more severe symptoms, including swelling of the brain and permanent disability

Prevention and treatment

- Treatment currently is directed at relieving symptoms, as there is no available vaccine

- Preventive measures include minimizing mosquito exposure by using insect repellents, avoiding standing water, covering exposed skin and installing window and door screens

Source: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention