Zika infection reduces fertility, lowers testosterone in male mice

Human studies needed to determine if men similarly affected

Huy MachThere is no treatment currently available to block Zika virus in a pregnant woman from infecting her fetus and potentially causing severe birth defects. Now, researchers have identified a human antibody that prevents, in pregnant mice, the fetus from becoming infected and the placenta from being damaged. The antibody also protects adult mice from Zika disease. Above, a researcher holds a tray of Zika virus growing in animal cells.

Most of the research to understand the consequences of Zika virus infection has focused on how the virus affects pregnant women and causes severe birth defects in their developing fetuses.

But a new study in mice suggests that Zika infection also may have worrisome consequences for men that interfere with their ability to have children. The research indicates that the virus targets the male reproductive system. Three weeks after male mice were infected with Zika, their testicles had shrunk, levels of their sex hormones had dropped and their fertility was reduced. Overall, these mice were less likely to impregnate female mice.

The study is published Oct. 31 in Nature.

“We undertook this study to understand the consequences of Zika virus infection in males,” said Michael Diamond, MD, PhD, a co-senior author on the study and the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine. “While our study was in mice – and with the caveat that we don’t yet know whether Zika has the same effect in men – it does suggest that men might face low testosterone levels and low sperm counts after Zika infection, affecting their fertility.”

The virus is known to persist in men’s semen for months. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that men who have traveled to a Zika-endemic region use condoms for six months, regardless of whether they have had symptoms of Zika infection. It is not known, however, what impact this lingering virus can have on men’s reproductive systems.

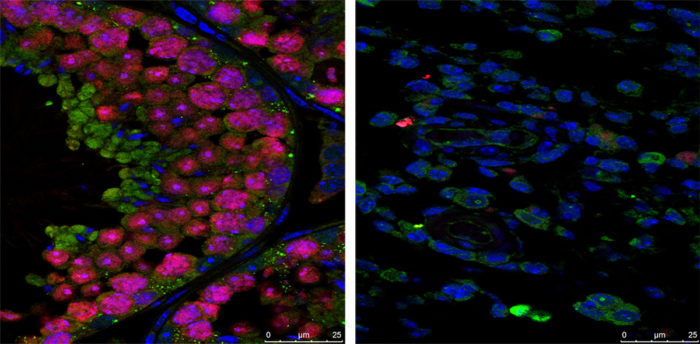

To find out how the Zika virus affects males, Diamond, co-senior author Kelle Moley, MD, the James P. Crane Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and colleagues injected male mice with the Zika virus. After one week, the virus had migrated to the testes, which bore microscopic signs of inflammation. After two weeks, the testicles were significantly smaller, their internal structure was collapsing, and many cells were dead or dying.

After three weeks, the mice’s testicles had shrunk to one-tenth their normal size and the internal structure was completely destroyed. The mice were monitored until six weeks, and in that time their testicles did not heal, even after the mice had cleared the virus from their bloodstreams.

Prabagaran Esakky

Prabagaran Esakky“We don’t know for certain if the damage is irreversible, but I expect so, because the cells that hold the internal structure in place have been infected and destroyed,” said Diamond, who is also a professor of pathology and immunology, and of molecular microbiology.

The structure of the testes depends on a type of cell called Sertoli cells, which maintain the barrier between the bloodstream and the testes and nourish developing sperm cells. Zika infects and kills Sertoli cells, the researchers found, and Sertoli cells don’t regenerate.

The testes normally produce sperm and testosterone, and as the mice’s testes sustained increasing levels of damage, their sperm counts and testosterone levels plummeted. By six weeks after infection, the number of motile sperm was down tenfold, and testosterone levels were similarly low.

When healthy females were mated with infected and uninfected male mice, the females paired with infected males were about four times less likely to become pregnant as those paired with uninfected males.

“This is the only virus I know of that causes such severe symptoms of infertility,” said Moley, a fertility specialist and director of the university’s Center for Reproductive Health Sciences. “There are very few microbes that can cross the barrier that separates the testes from the bloodstream to infect the testes directly.”

Prabagaran Esakky

Prabagaran EsakkyNo reports have been published linking infertility in men to Zika infection, but, Moley said, infertility can be a difficult symptom to pick up in epidemiologic surveys.

“People often don’t find out that they’re infertile until they try to have children, and that could be years or decades after infection,” Moley said. “I think it is more likely doctors will start seeing men with symptoms of low testosterone, and they will work backward to make the connection to Zika.”

Men with low testosterone may experience a low sex drive, erectile dysfunction, fatigue and loss of body hair and muscle mass. Low testosterone can be diagnosed with a simple blood test.

“If testosterone levels drop in men like they did in the mice, I think we’ll start to see men coming forward saying, ‘I don’t feel like myself,’ and we’ll find out about it that way,” Moley said. “You might also ask, ‘Wouldn’t a man notice if his testicles shrank?’ Well, probably. But we don’t really know how the severity in men might compare with the severity in mice. I assume that something is happening to the testes of men, but whether it’s as dramatic as in the mice is hard to say.”

Diamond and Moley said human studies in areas with high rates of Zika infection are needed to determine the impact of the virus on men’s reproductive health.

“Now that we know what can happen in a mouse, the question is, what happens in men and at what frequency?” Diamond said. “We don’t know what proportion of infected men get persistently infected, or whether shorter-term infections also can have consequences for sperm count and fertility. These are things we need to know.”

Prabagaran Esakky/Eric Young

Prabagaran Esakky/Eric Young