COVID-19 can kill heart muscle cells, interfere with contraction

Study reveals details of how coronavirus infects heart; models of tissue damage may help develop potential therapies

Lina Greenberg

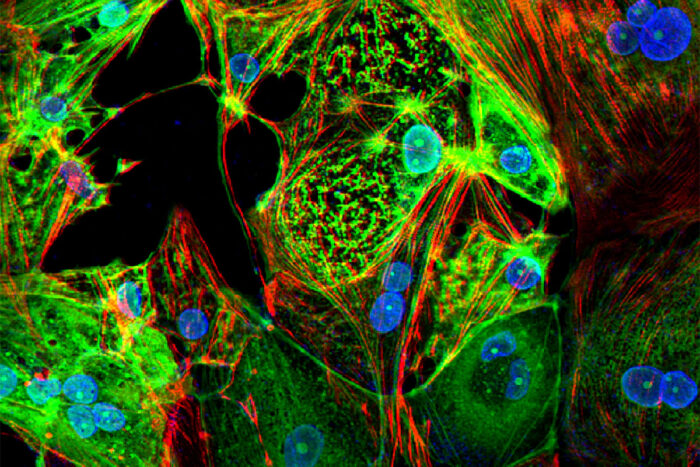

Lina GreenbergA study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis provides evidence that the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 can invade and replicate inside heart muscle cells, causing cell death and interfering with heart muscle contraction. The image of engineered heart tissue shows human heart muscle cells (red) infected with SARS-CoV-2 (green).

Since early in the pandemic, COVID-19 has been associated with heart problems, including reduced ability to pump blood and abnormal heart rhythms. But it’s been an open question whether these problems are caused by the virus infecting the heart, or an inflammatory response to viral infection elsewhere in the body. Such details have implications for understanding how best to treat coronavirus infections that affect the heart.

A new study from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis provides evidence that COVID-19 patients’ heart damage is caused by the virus invading and replicating inside heart muscle cells, leading to cell death and interfering with heart muscle contraction. The researchers used stem cells to engineer heart tissue that models the human infection and could help in studying the disease and developing possible therapies.

The study is published Feb. 26 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Basic to Translational Science.

“Early on in the pandemic, we had evidence that this coronavirus can cause heart failure or cardiac injury in generally healthy people, which was alarming to the cardiology community,” said senior author Kory J. Lavine, MD, PhD, an associate professor of medicine. “Even some college athletes who had been cleared to go back to competitive athletics after COVID-19 infection later showed scarring in the heart. There has been debate over whether this is due to direct infection of the heart or due to a systemic inflammatory response that occurs because of the lung infection.

“Our study is unique because it definitively shows that, in patients with COVID-19 who developed heart failure, the virus infects the heart, specifically heart muscle cells.”

Lavine and his colleagues — including collaborators Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor of Medicine, and Michael J. Greenberg, PhD, an assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics — also used stem cells to engineer tissue that models how human heart tissue contracts. Studying these heart tissue models, they determined that viral infection not only kills heart muscle cells but destroys the muscle fiber units responsible for heart muscle contraction.

They also showed that this cell death and loss of heart muscle fibers can happen even in the absence of inflammation.

“Inflammation can be a second hit on top of damage caused by the virus, but the inflammation itself is not the initial cause of the heart injury,” Lavine said.

Other viral infections have long been associated with heart damage, but Lavine said SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is unique in the effect it has on the heart, especially in the immune cells that respond to the infection. In COVID-19, immune cells called macrophages, monocytes and dendritic cells dominate the immune response. For most other viruses that affect the heart, the immune system’s T cells and B cells are on the scene.

“COVID-19 is causing a different immune response in the heart compared with other viruses, and we don’t know what that means yet,” Lavine said. “In general, the immune cells seen responding to other viruses tend to be associated with a relatively short disease that resolves with supportive care. But the immune cells we see in COVID-19 heart patients tend to be associated with a chronic condition that can have long-term consequences. These are associations, so we will need more research to understand what is happening.”

Part of the reason these questions of causation in heart damage have been hard to answer is the difficulty in studying heart tissue from COVID-19 patients. The researchers were able to validate their findings by studying tissue from four COVID-19 patients who had heart injury associated with the infection, but more research is needed.

To that end, Lavine and Diamond, are working to develop a mouse model of the heart injury. To emphasize the urgency of the work, Lavine pointed to the insidious nature of the heart damage COVID-19 can cause.

“Even young people who had very mild symptoms can develop heart problems later on that limit their exercise capacity,” Lavine said. “We want to understand what’s happening so we can prevent it or treat it. In the meantime, we want everyone to take this virus seriously and do their best to take precautions and stop the spread, so we don’t have an even larger epidemic of preventable heart disease in the future.”